digital textuality

Spotlight: Jeff Binder and the Distance Machine

On 28, Sep 2017 | In Spotlight | By Jojo Karlin

Creator: Jeffrey M. Binder

Project: The Distance Machine

Discipline: English

Campus: GC & Queens

Follow: @JeffMBinder

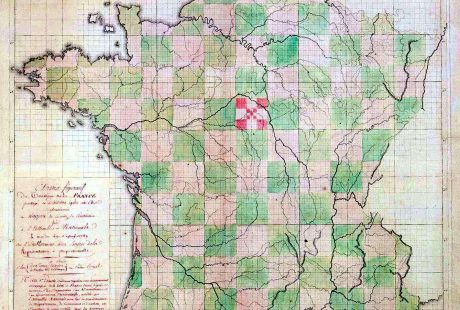

a “geometrical” approach to defining the administrative divisions of France, to which Burke took exception.

The Distance Machine is a new way of visualizing the linguistic changes that we have to grapple with while reading texts from the past. It uses a statistical model to determine when words either became common or ceased to be common in several large collections of books, including Google’s Ngrams data and the publicly available part of the Early English Books Online collection. This gives an approximate sense of when archaic words like thou cease to appear in these collections and when distinctively modern words—like computer—come into common use. Using this information, it shows you (right in your web browser) which words in a text might have stood out as unusual, novel, or specialized to readers encountering it at a given point in the past.

Last year, a paper on this project, “‘The General Practice of the Nation’: Walt Whitman, Language, and Computerized Search in the Nineteenth-Century Archive,” appeared in the journal American Literature. Since then, I used the Distance Machine in a study of representations of land in eighteenth-century America and France, which I presented at the Northeast MLA conference. In the NEMLA paper, I argue that the word location, which appears at several points in Thomas Jefferson’s writings, was politically charged in the eighteenth century, indicating a way of thinking about land that defines places by projecting a Cartesian grid onto the landscape—a practice that, Edmund Burke argued, was like treating one’s own country as a country of conquest. The example of the word location reveals a way in which the new linguistic forms introduced by the Enlightenment have now become so familiar that they are almost invisible to contemporary readers.

Paying attention to language change using tools like the Distance Machine, I suggest, can help us recover some of the lost sense of novelty that texts from the past once had. Since the linguistic knowledge with which we in the twenty-first century read texts from past periods is, in part, a product of the historical processes that were at work in those periods, there is a danger that we tacitly give preference to the sides of political debates that won out. To resist this possibility, it is necessary to become a little less confident in our ability to understand the language of the past.

Welcome to the blog of the CUNY DHI, an effort to build momentum and community around Digital Humanities practitioners at CUNY. We hope you'll join us at our upcoming events and that you'll follow this blog to hear about the latest news in the field.

Welcome to the blog of the CUNY DHI, an effort to build momentum and community around Digital Humanities practitioners at CUNY. We hope you'll join us at our upcoming events and that you'll follow this blog to hear about the latest news in the field.

Recent Comments